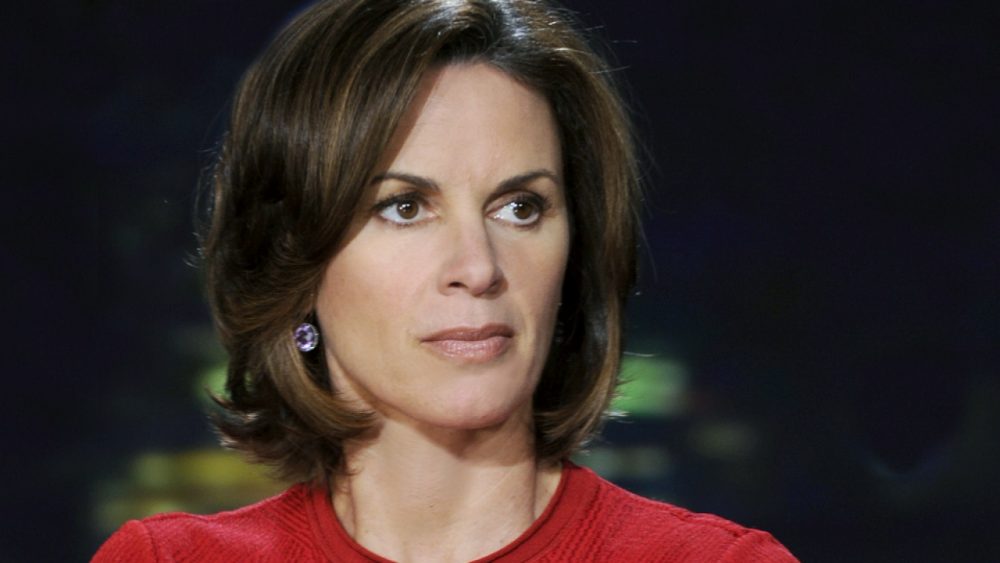

I can feel it coming, like a wave. My heart beats faster, my head pounds, my stomach churns, fear surges through me. It can happen in the middle of a busy day at work at the ABC television news magazine 20/20 or at home with the boys.

There was a time not so long ago that I would have reached for the bottle of wine in the fridge—or the bottle I’d hidden underneath the bathroom sink. Now I’ve found something that works much better. Something that helps me live, not die—the powerful weapon of daily prayer.

I don’t know if I was born an alcoholic, but I was definitely born anxious. The alcoholism came later in life, after years of drinking on the sly. But the anxiety? It was there from the start, as if it was part of the essence of me.

I grew up in a very Catholic home. My dad was in the Army, and our family’s involvement in the church was our spiritual constant as we moved from base to base. In the late sixties, we moved to Okinawa. My dad was sent to Vietnam, to Saigon, leaving my mom and my younger brother, Chris, and me in Japan.

My mom was pregnant with my little sister, and in order to stay on the island she had to work every day, leaving us with a babysitter. Each morning I would panic. I would chase after her, crying, begging her not to go, grabbing at her skirt, digging in my heels, holding her legs until she peeled away my fingers.

On the night Mom gave birth to my sister, I looked out the window from my bunk bed and saw her walking to the car, clutching her stomach with one hand, carrying a bag with the other. I knew she needed to go to the hospital, but I could not contain my panic. I jumped out of bed and ran to the door.

I was stopped by a neighbor who had come over to look after us. “What’s the matter with you?” she said. “Go back to bed. Stop making a scene.”

I was only six, but the message sank in, imprinted on me: My anxiety, my panic, was something shameful… something to be hidden at all costs. And the costs would prove huge. I white-knuckled my way through anxiety during childhood and adolescence.

My dad’s Army postings meant homes on nine different bases. I went to eight different schools. I wasn’t wise enough to turn to prayer to deal with stress and panic. I learned to survive the attacks in secret, to bury my feelings.

I thrived academically, graduating from the University of Missouri’s top-ranked journalism school and starting a career in TV broadcasting. I prided myself on being cool in a crunch, a real professional. My secret was safe. Except once.

It was a Saturday night in Chicago in the early 1990s. I was working at WBBM, doing the 10:00 p.m. newscast with a veteran coanchor. All at once I felt like I couldn’t breathe. My hands trembled. I was queasy. I was sure I was going to vomit. I clenched my jaw and stopped reading the teleprompter right in the middle of a story.

The air went dead. Hundreds of thousands of viewers could see the real me, exposed. A full-blown panic attack on air. So much for being a cool professional.

My coanchor jumped in and read my part. We went to commercial and he glared at me, furious, and then—like that neighbor all those years ago in Okinawa—demanded to know what was wrong with me. I had no answer, at least not one I was willing to share. I’d violated one of my basic rules: Don’t make a scene. I vowed it would never happen again.

I was careful never to do a broadcast on a full stomach. I discovered that a beta-blocker could help. Better yet, off air, when I needed to unwind, a glass of wine hit the spot. It was like turning off the worry switch. “Just wine” was my rule, though. Nothing stronger.

I put a lot of pressure on myself. Good enough wasn’t good enough; everything I did had to be perfect. The more successful I became, it seemed, the more I had to hide. And the more I hid, the more I cut myself off from other people and from God. When I prayed, it was reactive—pleading to get through a stressful day or through a panic attack without anyone knowing—not a true relationship with God.

Then came the job at 20/20. It was a huge break. And there was a price. Besides the long hours, I’d have to do a ton of traveling. More hours on a plane, trapped in a tube at 30,000 feet. Reason enough for anxiety.

After suffering a particularly harrowing panic attack on one flight— sweating, hyperventilating—I went to a doctor and for the first time confessed my anxiety. He gave me a prescription for anti-anxiety medication. It helped. So did the wine the helpful flight attendants brought to my seat.

But you can’t hide from everyone, especially someone you love and trust. I met Marc after I moved to New York and soon we were married. We had two beautiful boys. Marc was the only one I had confided the secret of my anxiety attacks to. He countered with a truth I wasn’t ready to believe. “I think you drink too much,” he said.

“Are you kidding?” I was furious. No one had ever said that to me before. No one knew how much I drank. How dare he!

I walked right out of the room. Me, a drunk? I was an Emmy-winning broadcaster on network TV, meeting deadlines left and right, appearing on air night after night. I could cut back or quit anytime I wanted. No problem. What alcoholic could do that?

Since Marc didn’t like to see me drinking, I would sometimes stop in a little bar on my way home from work and have a glass—or two—of wine there… draining the day’s tension. But that didn’t feel quite as nice. I felt pathetic, sitting there alone. Sometimes I would pretend I was waiting for a friend.

“That’s all right,” I would say into my dead cell phone. “I just sat down. Take your time.”

Things got out of control so slowly that I convinced myself there was no problem. I’d go on a trip for work, drink heavily at night after the shoot, then pull it together in time to be on camera in the morning. I told myself I was good at maintaining the work-life balance. But then, on a long-anticipated family vacation, I ended up spending most of the time in bed, sleeping off my hangovers from raiding the minibar.

The shame was incredible, palpable, almost as bad as a panic attack. It was like a moral panic attack. I checked into a rehab facility right away. But only for a couple of weeks. Doing the full 28-day program would have meant revealing to my bosses at the network that I had a problem. So I told them I needed surgery—nothing life-threatening. It was a flat-out lie.

The rehab place was beautiful and the people were kind. They helped me reconnect with God for the first time in years. Not that I was ready to turn my will and my life over to a higher power. That wasn’t happening.

Two months later I was drinking again. I went back into rehab for a longer stint, the full 28-day program. There was so much I had to deal with, especially my feelings. I’d spent the majority of my life hiding.

Recovery meant getting honest, most of all with myself. I had to dig deep. I had to confront why I’d become so dependent on alcohol. People all around me spoke openly about themselves. I had to be open too. It was hard, maybe the hardest thing I ever did.

One day close to the end of my stay I spoke to the group. “I’m really scared,” I said. “I’m afraid of going back to my life, of being surrounded by stress and temptation. I’m afraid of my anxiety and what I will do to escape it.”

Tears came to my eyes. I rarely allowed myself to cry in front of anybody. I thought people would be embarrassed seeing me cry. I expected to be reprimanded, the way I had been by that neighbor all those years ago. Instead, my tears were met with understanding and compassion. Was it possible that I could reveal the worst about myself and still be loved?

“God bless you,” someone said. “Pray to God to help you.” Prayer was the tool I could take with me, prayer whenever the stress hit, prayer when the desire to reach for a glass of wine overcame me. This time I managed to hold it together back in New York City. For a while, at least.

I was so glad to be sober, so glad to be back at work. But the stresses were still there, and when I dropped into a recovery meeting with other alcoholics, as I’d promised I would, I would sit in the back, hiding under a hat, never speaking out, never revealing that I was struggling like everyone else in the room. Gradually I stopped going to meetings, stopped reaching out to friends in the program.

Then came the first setback. I couldn’t handle it sober. I thought the anxiety was going to kill me. I didn’t pray. I walked into a bar and ordered a drink. It wasn’t so much the glass of wine that was my downfall, but that I was no longer praying daily or talking with other people in recovery. My isolation was growing again.

Soon I was sneaking wine regularly and I suppose it was inevitable that I would show up for work drunk, which I did.

I hit absolute bottom. Back in Chicago I’d fallen apart on the air. This was worse. Much worse. Yes, the cure turned out to be worse than the disease.

There was no hiding it. Now everyone knew I was going into rehab—again. I had to issue a public statement: “Like so many people, I am dealing with addiction.” My shameful secret was there for all to see. “I am in treatment….”

This rehab place was much tougher than the other one. It was grim, and I felt hopeless there. Reaching out to my parents and my brother and sister was what saved me.

There was a weekend when family members came. Family histories—and family secrets—were revealed and explored in a therapeutic setting. My brother, Chris, my sister, Aimie, and both of our parents made the trip. For the first time ever we talked about our childhood.

Mom and Dad discussed the trials of raising us kids when Dad was in Vietnam and Mom was all on her own in Japan. They knew how hard it was on us kids. My mother had agonized over my daily panic attacks when she left me in the morning. She admitted she didn’t comfort me. She didn’t know how. The U.S. military was not helping Vietnam vets with their PTSD then. There certainly was no one to help their families with such issues.

“I wished I could help you,” my mom said. “I felt so helpless. I didn’t know what to do.” She put her hand on mine. “I’m so sorry.”

Those words meant everything. They validated my feelings. An enormous weight lifted from me. A burden I’d been carrying for forty-some years. It was all right to be afraid and to talk about it—to God and to other people. Anxiety wasn’t going to kill me, but isolation would.

I discovered that prayer is my most powerful weapon. Not just at moments of high anxiety, moments when I feel on the verge of losing control, but all the time, turning to God for reassurance and strength as I move through my day.

I have a real relationship with him now, an awareness that it’s not just me on my own, that there’s a higher power at work in my life—every moment, every day. I end each day by making a list of all the things that I’m thankful for. Gratitude is a potent antidote to fear.

I am grateful to my family, grateful for my job and especially grateful to all those people who have supported me and loved me when I doubted I deserved love. I don’t hide in the back of recovery meetings anymore but sit in the front, glad to help as I have been helped. Anxiety is always there, but prayer is too. It has given me the power to say no to drinking and the power to say yes to life.